On North Carolina’s rivers and streams, the cleanup of Helene’s fury seems never-ending

WOODFIN, N.C. (AP) — Bracing himself against the current in waist-deep water, Clancy Loorham wrestles a broken length of PVC pipe from the rocky bottom of the French Broad River and peers inside.

“I got a catfish in the pipe,” the 27-year-old with wispy beard and mustache shouted to fellow cleanup workers floating nearby in rafts, canoes and kayaks piled with plastic pipe and other human-made detritus. “He’s right here. I’m looking him in the eyes!”

It’s been just a year since floodwaters from the remnants of Hurricane Helene washed these pipes out of a nearby factory with such force that some pieces ended up in Douglas Lake, about 90 miles (145 kilometers) away in Tennessee. But they’re already slick with algae and filled with river silt — and creatures.

Helene killed more than 250 people and caused nearly $80 billion in damage from Florida to the Carolinas. In the North Carolina mountains, rains of up to 30 inches (76 centimeters) turned gentle streams into torrents that swept away trees, boulders, homes and vehicles, shattered century-old flood records, and in some places carved out new channels.

In the haste to rescue people and restore their lives to some semblance of normalcy, some fear the recovery efforts compounded Helene’s impact on the ecosystem. Contractors hired to remove vehicles, shipping containers, shattered houses and other large debris from waterways sometimes damaged sensitive habitat.

“They were using the river almost as a highway in some situations,” said Peter Raabe, Southeast regional director for the conservation group American Rivers.

Conservationists found instances of contractors cutting down healthy trees and removing live root balls, said Jon Stamper, river cleanup coordinator for MountainTrue, the North Carolina-based nonprofit conducting the French Broad work.

“Those trees kind of create fish habitats,” he said. “They slow the flow of water down. They’re an important part of a river system, and we’ve seen kind of a disregard for that.”

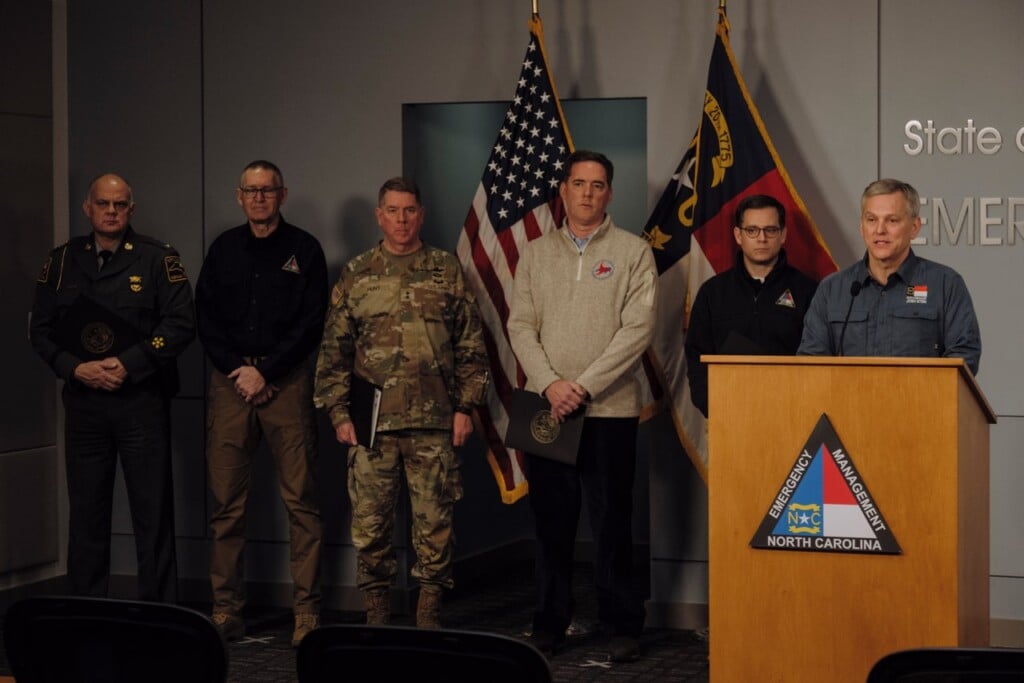

The Army Corps of Engineers said in a statement that debris removal missions “are often challenging” due to the large volume storms can leave behind across a wide area. The Corps said it trains its contractors to minimize disturbances to waterways and to prevent harm to wildlife. North Carolina Emergency Management said debris removal after Helene took into account safety and the environment, and that projects reimbursed by the Federal Emergency Management Agency met that agency’s standards for minimizing impact.

Battered first by the storm, and then by the cleanup

Hannah Woodburn, who tracks the headwaters and tributaries of the New River as MountainTrue’s Upper New Riverkeeper, said waters are much muddier since Helene, both from storm-related vegetation loss and from heavy machinery used during cleanup.

She said it’s been bad for the eastern hellbender, a “species of special concern” in North Carolina. It’s one of only three giant salamanders found in the world, growing up to 2 feet (61 centimeters) long and weighing more than 3 pounds (1.4 kilograms).

“After the storm, we had so many reports and pictures of dead hellbenders, some nearly a mile from the stream once the waters receded,” said Woodburn.

Of even greater concern is the Appalachian elktoe, a federally endangered mussel found only in the mountains of North Carolina and eastern Tennessee. Helene hurt the Appalachian elktoe, but it also suffered from human-caused damage, said Mike Perkins, a state biologist.

Perkins said some contractors coordinated with conservation teams ahead of river cleanups and took precautions. Others were not so careful.

He described snorkeling in the cold waters of the Little River and “finding crushed individuals, some of them still barely alive, some with their insides hanging out.” On that river, workers moved 60 Appalachian elktoe to a refuge site upstream. On the South Toe River, home to one of the most important populations, biologists collected a dozen and took them to a hatchery to store in tanks until it’s safe to return them to the wild.

“It was shocking and unprecedented in my professional line of work in 15 years,” Perkins said of the incident. “There’s all of these processes in place to prevent this secondary tragedy from happening, and none of it happened.”

Andrea Leslie, mountain habitat conservation coordinator with the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission, said she hopes the experience can inform future recovery efforts.

“To a certain degree, you can’t do this perfectly,” she said. “They’re in emergency mode. They’re working to make sure that people are safe and that infrastructure is safe. And it’s a big, complicated process. And there are multiple places in my observation where we could shift things to be more careful.”

Humans along the river are still recovering, too

Like the hellbender and the Appalachian elktoe, humans cling to the river, too.

Vickie and Paul Revis’ home sat beside old U.S. 70 in a bend of the Swannanoa River. As Helene swept through, the Swannanoa took their home and scraped away a big chunk of their half-acre lot.

With the land paid for and no flood insurance payment to move away, they decided to stay put.

“When you own it and you’re not rich, you know, you can’t,” Vickie Revis said, staring across the river at a row of condemned commercial buildings.

After a year in a donated camper, they’ll soon move into their new house — a double-wide modular home, also donated by a local Christian charity. It sits atop a 6-foot mound that Paul Revis piled up near the front of the property, farther from the river.

Using rock, fill dirt and broken concrete dumped on his property by friendly debris-removal contractors, Paul has reclaimed the frontage the Swannanoa took. His wife planted it with marigolds for beauty and a weeping willow for stability. And they’ve purchased flood insurance.

“I hope I never see another one in my lifetime, and I’m hoping that if I do, it does hold up,” Vickie said. “I mean, that’s all we can (do). Mother Nature does whatever she wants to do, and you just have to roll with it.”

Tons of debris pulled out, tons still to go

Back on the French Broad, the tedious cleanup work continues. Many on the crew are rafting guides knocked out of work by the storm.

MountainTrue got a $10 million, 18-month grant from the state for the painstaking work of pulling small debris from the rivers and streams. Since July, teams have removed more than 75 tons from about a dozen rivers across five watersheds.

Red-tailed hawks and osprey circle high overhead as the flotilla glides past banks lined with willow, sourwood and sycamore, ablaze with goldenrod and jewelweed. That peacefulness belies its fury of a year ago that upended so many lives.

“There are so many people who are living in western North Carolina right now that feel very afraid of our rivers,” said Liz McGuirl, a crew member who managed a hair salon before Helene put her out of work. “They feel hurt. They feel betrayed.”

Downstream, as McGuirl hauled up a length of pipe, another catfish swam out.

“We’re creating a habitat, but it’s just the wrong habitat,” crew leader Leslie Beninato said ruefully. “I’d like to give them a tree as a home, maybe, instead of a pipe.”