Why no hurricanes made landfall in the US in 2025

(ABC NEWS) – The 2025 Atlantic hurricane season proved to be consequential, even though no hurricanes made landfall in the U.S for the first time since 2015.

Three Category 5 hurricanes formed during this past hurricane season, tying for the second-most on record in the Atlantic basin. The only other season that saw more Category 5 storms was in 2005, when there were four Category 5 storms.

Last month, Hurricane Melissa became one of the most powerful hurricanes on record to make landfall in the Atlantic basin, ranking with Hurricane Dorian (2019) and the “Labor Day” hurricane (1935) for the strongest sustained winds at landfall.

Sunday marks the official end of the Atlantic hurricane season, and for the first time in a decade, not a single hurricane made landfall in the U.S., according to the National Hurricane Center (NHC).

Prior to the start of the season, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) predicted above average activity in its initial Atlantic hurricane season outlook, with 13 to 19 named storms, six to 10 hurricanes, and three to five major hurricanes, Category 3 or stronger.

This season, the Atlantic basin produced 13 named storms, five of which became hurricanes. This included four major hurricanes with maximum sustained winds reaching 111 mph or greater.

An average season typically sees 14 named storms, seven hurricanes and three major hurricanes.

The National Hurricane Center uses Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) to measure hurricane season activity, not just the number of named storms, which also takes into account the longevity and intensity of tropical cyclones. By this measure, the 2025 Atlantic hurricane season ranked slightly above average since the hurricanes that did form were exceptionally strong. Nine out of the past 10 Atlantic hurricane seasons featured above average activity.

The first named storm of the season, Tropical Storm Andrea, formed on June 23. Tropical storms Barry and Chantal quickly followed. Tropical Storm Chantal was the only system to make landfall in the U.S., bringing excessive rainfall and flooding to North Carolina in early July.

Hurricane Erin became the first Category 5 hurricane of the season on Aug. 16. The storm brought destructive coastal erosion and storm surge to the North Carolina Outer Banks and rough surf and rip currents along the East Coast.

After Tropical Storm Fernand, which formed on Aug. 23 and remained active in the central Atlantic through the 27th, the Atlantic basin saw no named storms for three weeks, a lull that spanned the climatological peak of the hurricane season on Sept. 10.

Large-scale environmental conditions gradually became more favorable for tropical cyclone activity by the second half of September, and Tropical Storm Gabrielle formed on Sept. 17, the first of seven named storms to develop through the end of October.

Roughly 60% of tropical activity occurs after Sept. 10, on average, according to the NHC.

Considering that a portion of this year’s hurricane season occurred during the longest federal government shutdown in history, experts say it is fortunate that none of the storms hit the U.S.

“The forecasters at the NHC kept working, but without pay,” said Marc Alessi, climate attribution fellow at the Union of Concerned Scientists. “The U.S. got lucky that no hurricanes made landfall during the government shutdown. FEMA response would have been limited.”

It was largely due to a combination of favorable conditions and a bit of luck. Prevailing winds and weather patterns steered storms away from the coast, and many variables aligned at the right times, keeping hurricanes from making landfall.

“It’s a function of the steering patterns and synoptic weather patterns of the year,” Marshall Shepherd, director of the Atmospheric Sciences Program for the University of Georgia and former president of the American Meteorological Society, told ABC News.

It was beneficial that large-scale environmental conditions were unfavorable for development in the weeks leading up to the peak of the season. Persistent dry air and other unfavorable atmospheric conditions hindered storm development during a historically busy timeframe.

Many of the storms that did form followed a similar path, curving away from the U.S. coastline and toward Bermuda. An unusually persistent upper-level trough, or area of lower pressure, sat over the eastern U.S. throughout much of the season, bringing seasonably mild temperatures by late summer. The recurring trough frequently pushed the jet stream south, helping curve storms northward parallel to the East Coast and then out to sea, following the prevailing west to east wind pattern.

The trough also weakened the western side of the Bermuda High; the dominant high-pressure system located over the Atlantic Ocean that usually helps steer weather systems. When the Bermuda High is strong, storms are pushed farther west toward the East Coast and the Gulf. However, when it is weaker, they tend to turn northward earlier. This season, the weakened Bermuda High, combined with a dip in the jet stream, deflected storms away from land.

Another factor that kept the U.S. hurricane-free this year was the Fujiwhara effect, a rare occurrence in the Atlantic basin.

The Fujiwhara effect occurs when two tropical cyclones within several hundred miles of each other begin to interact and rotate around a common midpoint, according to NOAA. In this instance, Hurricanes Imelda and Humberto were churning through the western Atlantic at the same time. The stronger storm, Humberto, exerted more influence and pulled the weaker Imelda away from the U.S. before it got too close to the coast.

The meteorological phenomenon played a crucial role in late September as Imelda moved across the Bahamas and edged closer to the southeastern U.S. coast.

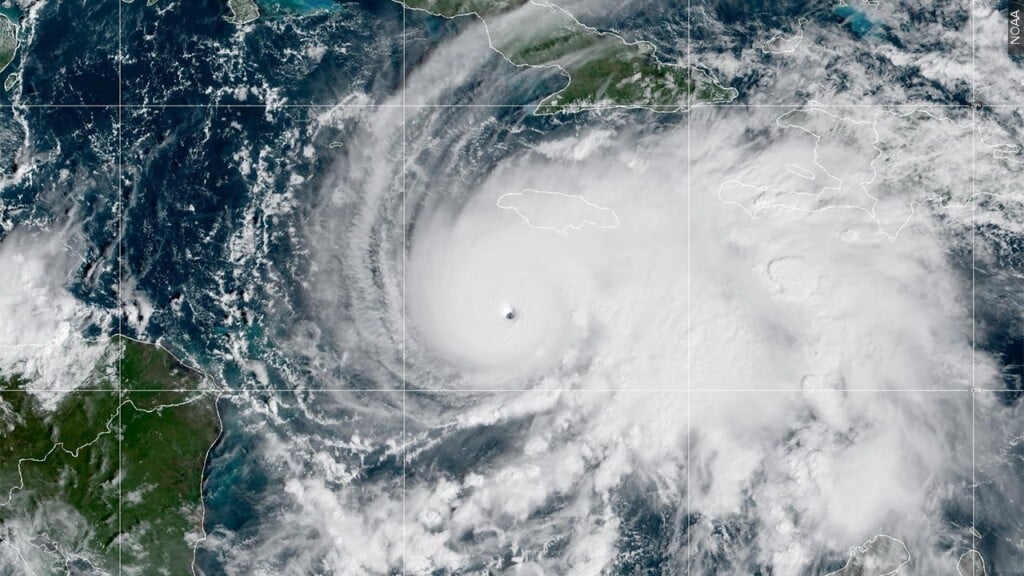

The final named storm, and arguably the most remarkable, was Melissa. It became a tropical storm on Oct. 21 over the central Caribbean Sea. It rapidly intensified into a Category 5 hurricane, ultimately becoming one of the most powerful hurricanes on record to make landfall in the Atlantic basin.

Melissa became the strongest hurricane on record to make landfall Jamaica, surpassing Hurricane Gilbert in September 1988. The storm came ashore in southwestern Jamaica near New Hope on Oct. 28 as a Category 5 hurricane, with maximum sustained winds of 185 mph, according to the NHC. It then swept across western Jamaica, unleashing destructive winds and catastrophic flash flooding.

At least 45 people in Jamaica lost their lives as a result of the storm, according to local officials.

This season offers a glimpse into how human-amplified climate change could influence tropical activity in the coming decades. While the total number of tropical cyclones is expected to remain steady or even decrease slightly, the storms that do form are likely to be more intense, according to climate scientists.

Thirteen named storms in one season falls far short of the 30 that occurred in 2020. However, the three Category 5 hurricanes that formed in 2025 rank as the second-most on record in the Atlantic basin, surpassed only by 2005, which saw four.

“Not only are we starting to see more and more intense and powerful hurricanes, but we’re also seeing more hurricanes undergo rapid intensification,” Alessi said.

Human-caused climate change has led to substantial ocean warming, which fuels hurricane intensification. More than 90% of the excess heat trapped by greenhouse gases has been absorbed by the oceans, creating conditions that favor rapid intensification and stronger peak winds. As a result, more storms are reaching major hurricane strength compared to past decades, the latest research shows.

Hurricane Melissa also underscores the heightened vulnerability of island nations like Jamaica to the impacts of human-amplified climate change. Small islands face higher risks compared with larger land masses because of their limited size and exposure to surrounding oceans, according to the Meteorological Service of Jamaica.

The changing climate is also amplifying the indirect effects of tropical systems that remain well offshore, making coastal areas more vulnerable. Sea level rise and more intense storms increase the risks of flooding, erosion, and shoreline change, according to the federal government’s Fifth National Climate Assessment. Human modifications to coastal landscapes, such as seawalls and levees, can worsen flood risks, accelerate erosion and hinder the ability of coastal ecosystems to naturally adapt.